More than a Feeling

The with-ness of God, the Lord's baptism, and the Holy Spirit

A note on this newsletter in 2024

Before today’s post, I’m inspired by Aaron Hann’s “Why I Write” to say a huge thank you to all of you who read my stuff and share an update on where this is going.

In August, I started as a pastor of a small church in northern Vermont. I preach most Sundays, so much of what I share here are sermon adaptations that follow along with the Revised Common Lectionary calendar, readings collectively read across many different denominations. In 2024, these weekly scriptural reflections will be the core of what I do here. While the actual sermons deviate from my posts, these weekly proto-sermons are a way for me to share my theologizing out loud, often with more personal details and thorough exegesis than I might include in a sermon proper. On weeks I’m off from preaching, these posts might be a little shorter (“and the people rejoiced”), but writing these are a spiritual discipline and a way to synergize my local congregation with a broader spiritual conversation. Again, I’m grateful for everyone who engages.

In addition to these weekly posts, I will occasionally share other topical pieces. I know some of you signed up for this newsletter as part of my other newsletter, Psychedelic Candor, writing on contemporary issues with psychedelic medicalization and religion. While my writing here can still be described as post-psychedelic, sometimes drawing upon those experiences like I will today, I don’t plan on doing focused writing about that here. Instead, I am especially excited to flesh out something called Reformed mysticism. I’ll have more to say on this in a future piece, but this is maybe the best name for my spiritual disposition.

I also want to do a better job of encouraging comments and feedback more explicitly, so let’s start now: is there anything you’d like to see more in this newsletter? Please leave a comment below, or anytime in the future, and please share any of your thoughts that a piece might inspire. It is awesome for me to hear your engagement, but I don’t always know what’s going to be the juiciest for you.

If you like what you read here and you feel like it adds value to your life, your generosity is a tremendous help to making this part of my life sustainable. Again, thank you to those who have already supported. Now, in the words of Trey Anastasio, “For those of you who want to take off, take off…but for those of you that just want to dance to the funk, we're going to stay around and keep grooving.” On with the funk.

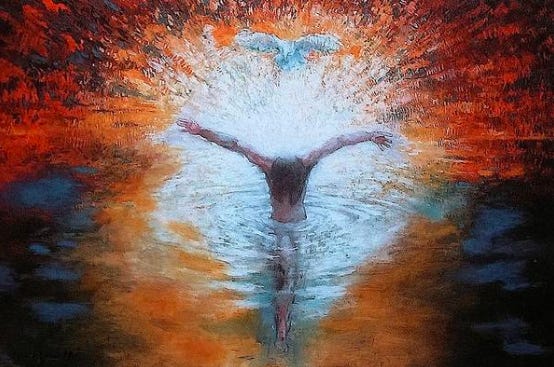

The Water, the Voice, and the Bird

“I have baptized you with water; but he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit."

In those days Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan. And just as he was coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens torn apart and the Spirit descending like a dove on him. And a voice came from heaven, "You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased."

Mark 1:8-10

It was just two weeks ago we met baby Emmanuel, little ol’ “God with us,” and now we’re already on Jesus’ baptism. God’s time, in all its fullness, sometimes moves fast. The last time we had a flashing-neon biblical dove was Noah’s time, when God was just starting to realize humans can be so terrible it can even surprise God. As St. Ambrose said in recapping God’s posture before the flood, “ ‘My Spirit,’ says God, ‘shall not remain among men, because they are flesh.’ ” But God’s time kept moving.

For those who have been reading along, Mark’s baptismal recap is the third time in about six weeks we’ve read about John the Baptist and his baptism for the forgiveness of sins. But now we have questions that have puzzled and inspired Christians since the first ones: what is the difference between John’s baptism and Christ’s? Why did Christ get baptized by John, and why does it matter to us?

Part of the answer is obvious, but then mysterious again: it’s the presence of the Holy Spirit, stupid. But this only matters to us because of what it says of our shared fundamental relationship to God. If John’s baptism is about our actions restoring our relationship to God, Christ’s baptism is not about what we do, but God’s work in the movement of the wild Spirit. We see this in a story from the Early Church:

Now there came to Ephesus a Jew named Apollos from Alexandria. He was an eloquent man, well-versed in the scriptures. He had been instructed in the Way of the Lord, and he spoke with burning enthusiasm and taught accurately the things concerning Jesus, though he knew only the baptism of John. He began to speak boldly in the synagogue, but when Priscilla and Aquila heard him they took him aside and explained the Way of God to him more accurately. …

While Apollos was in Corinth, Paul passed through the interior regions and came to Ephesus, where he found some disciples. He said to them, "Did you receive the Holy Spirit when you became believers?" They replied, "No, we have not even heard that there is a Holy Spirit." Then he said, "Into what then were you baptized?" They answered, "Into John's baptism." Paul said, "John baptized with the baptism of repentance, telling the people to believe in the one who was to come after him, that is, in Jesus." On hearing this, they were baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus. When Paul had laid his hands on them, the Holy Spirit came upon them, and they spoke in tongues and prophesied.

Acts 18:24-26, 19:1-6

In a book full of martyrs, miracles, church fights, and street riots, this story from the Acts of the Apostles is the wildest mystery yet of how a church disagreement can go right. As Fr. Aaron and Melissa Burt of At Home with the Lectionary podcast pointed out, we get an image of how to kindly correct each other’s spiritual blind spots better than it ever goes on Twitter. There are other times in Acts when a strong rebuke of false teachers is called for, as was the case with the sorcerer-guru Simon Magus trying to buy the power of the Holy Spirit so he could manipulate it. But in Apollos’ case, he was ignorant but sincere, humble, and open to learning—ah, yes, just like all of us all the time.

The more important issue at stake here is how the Early Church clarifies the nature of John’s baptism and its difference from Christ’s baptism. It’s a question that Matthew says stumped Pharisees, “Was John’s baptism from heaven or of human origin?”1 But before we think we’ve got one up on the Pharisees, this immediately gets confusing again because wait, didn’t Jesus receive John’s baptism? Let’s go deeper.

Two-for-One Baptism

The fundamental difference between John’s baptism and Christian baptism is what it says about our relationship to God.

John’s baptism is a relationship with God that reminds us of 1) our essential difference from God, and 2) our human-to-human solidarity with each other as sinners. These are not bad reminders at all, in fact, they’re transformative. This repentant baptism corrects our spiritual pride which falsely elevates us to God’s level, and it corrects our false superiority over each other—we all need washing in the same water. In its biblical context, John’s baptism is part of a long, sometimes strained, but ultimately intimate relationship of love between God and God’s people. This story is something like this: we are born in God’s love, but we fail over and over to live up to this love, and we keep showing we can’t keep the spiritual promises we make, and so we must return to God to restore and reconcile the distance we create between us and God. In repentance, we come back to right relationship with God, knowing we will fail again, but knowing God will forgive again. The practice of Christian confession still cherishes this lineage.

The Christian witness contains an additional belief that God no longer waits for us to repair our relationship. God came, is coming, and will come again for us as one of us.

So when Jesus asks the Pharisees a trick question—“Was John’s baptism from heaven or of human origin?”—the unspoken trick answer was “both,” for Christ chose to step into John’s baptism from heaven. It is a fractal reconciliation, where even the human means of restoration is reconciled with God’s. God has stepped into our human waters, enveloping himself in our sin. Before we can ask for grace and before we’re even aware of it, Grace is already seeking to dwell in us.

More than a Feeling

The second important issue in this Acts story is the nature and presence of our dovely friend the Holy Spirit.

Talking about the Holy Spirit is a challenge for Reformed mystics without resorting to vague aphorisms or, in Zen terms, “mistaking the finger for the moon.” Sometimes it’s a name modernists invoke as a kind of “God of the gaps” for novel secular things we like, but other times it drives charismatic revivals, sometimes from just a small spark of believers in a poor black Los Angeles neighborhood that spreads over the globe in less than a century. Some Christians barely know what to do with it at all; I grew up Presbyterian and am again, a branch of the Church that almost seems allergic to the Holy Spirit, so talking about it does not feel like home-field advantage.

While the stories in Acts offer charismatic signs of the presence of the Holy Spirit, a Reformed mystic might be cautious in making assumptions about how we define, identify, and label the Holy Spirit, because of what can go wrong when we mistakenly identify it with our states of consciousness via our pleasure, preferences, and feelings.

Quick story #1: a long time ago for my old podcast, a ex-Pentecostal friend told me about the pressure he felt as a kid to display spiritual gifts, including speaking in tongues. This, of course, did not foster an authentic relationship with God, but an inauthentic performativity in an environment ripe for spiritual abuse such as captured in the 2006 documentary Jesus Camp. While it’s far from every Pentecostal’s experience or understanding, it’s one problem of many that can arise.

One thing we can learn about the Holy Spirit in Christ’s baptism is that the movement of God is not dictated by our actions—God moves first, and last. If we think we can manufacture God through imitating signs of the Holy Spirit, or think it is detected in simply feeling ecstasy, we are more often than not fooling ourselves. And in the worst excesses of Christianity, we can be so certain the Holy Spirit is in our midst and in our capacity to conjure, like Simon Magus, we will do all manner of harm in the name of it.

Quick story #2: the hardest laugh I ever had in a psychedelic ceremony was when I first knew I wanted to be a Christian again. As the seeds of my reconversion sprouted, I had a mental blitz through halls of memories. As years of Angeleno nihilism, depression, and misguided self-pursuit flashed by, I had the thought, “the Holy Spirit was with me the whole time.” I began wheezing in joy. All the years I was horrible to myself and selfish to others, wrapped up in my own BS—as if I’m not anymore—all those years I had felt so, so far from God. But in that moment I realized I never actually was. Even though I hadn’t believed in God for almost a decade by then, I could see how God had never left me, I had just completely shut myself off to him. And yet God was still there. Through all the artists, the meditators, the comics, the spiritual seekers, the authentically nice (and sometimes a little less authentic) improvisers, the coworkers, the sex workers, the addicts, the writers…even in the obnoxiously wealthy and the cults of personality…even in the Hollywood dropout who had a float tank in his Highland Park backyard…and especially in the forgiveness from people I had no business getting, but even in the relationships that couldn’t be restored…even though I had felt so far from God for years, the Holy Spirit was there. It wasn’t visible to me; no tongues, no prophecies (at least, not accurate ones), no heavenly doves. But the Holy Spirit was, and is, there with all of us no matter how we’re feeling. Do not believe for a second that just because you are in depression, despair, or any other pain, that God has left you.

In my view, I would remain wrong for years after that belly laugh to the extent that I equated the Holy Spirit with psychedelicism or any spiritual practice, and especially to the extent I subconsciously believed I could summon it. The Holy Spirit came down in the Lord’s baptism not as a sign of high vibes, or even the feeling of grace, but in the actual true grace and sign of Christ’s body becoming one with ours.

The Holy Spirit was there in your pain, in your struggle, and even when you’ve been awful. In the Lord’s baptism, he is especially with our sin. God had said before the Flood, “My Spirit shall not remain among men, because they are flesh.” 2 But now he is doing a new thing.3 Noah’s dove flew over the waters and returned with a twig. In the Lord’s baptism, the dove flies over the waters to tell us, “My spirit will remain among you because you are flesh.”

“Because you are flesh,” says Jesus, “I will become flesh too, and you will be united in mine.”

Christ’s birth name Emmanuel means “God with us.”

Emmanuel doesn’t mean, “God is with you if you do it right.”

It isn’t “God is with you if you say the magic words.”

It isn’t “God is with you if you have the right spiritual map of the universe.”

It isn’t “God is with you if you donate,” or “if you go on my psychedelic retreat.”

It isn’t “God is with you if the music is amazing” (though it doesn’t hurt).

It isn’t “God is with you if you stop participating in evil.”

It even isn’t, “You know God is with you when you feel him.”

If Christmas was the Emmanuel announcement that God is present in the world, then the Lord’s baptism is God’s new kind of with-ness—God is with you even when you can’t feel him. The hidden dove is flying at you and around you all the time. Some days, you might find this to be a hilarious joy.

Matthew 21:23-27

Genesis 6:3

Isaiah 43:19

This was so meaningful for me. I agree with Aaron - would love to hear about your mystical experiences. I also had a similar break from church; God came and got me. So glad to gain spiritual wisdom and friendship.

Love this, Joe. Thankful for the reminder of God’s promised presence, even when what I feel is his absence. I look forward to learning more about your identification as a reformed mystic. If you hadn’t already planned to write on that, that’s what I would ask to hear more about, as somewhat of a wandering Presbyterian myself. Thanks also for the mention. It’s nice to be able to connect here with other writers.