Where is the Fire?

Another Advent question.

There are a lot of questions in Advent. It would make sense for a preacher to make them about the four themes of the Advent wreath’s candles—how do we keep hope? How do we make peace? How do we bring joy? How do we show love? These aren’t bad questions, but I’m not a preacher who always makes sense, so last week our first question of Advent was, “What are you waiting for?”

Scripture brings up even more questions throughout all our Advent readings. This week, Isaiah asks, "What shall I cry out?" Peter’s second letter asks, “Who are we supposed to be while we wait until the world is totally on fire?”

My second question is closer to Peter’s, but the world already feels on fire. For those of us who may walk in this world depressed, spiritually empty, trying to find meaning and motivation, we might even be just fine if it rained a little fire and sent this circus home. For those of us, the more potent Advent question than “who should I be” is, “Where the hell is God? Where is that fire? Where is The Fire?”

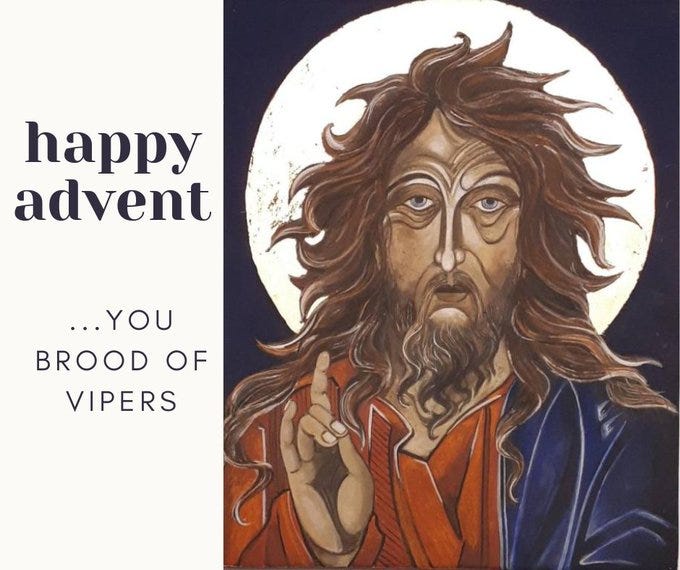

The Wild Saint of Advent

To answer this, let us turn to the guy who pastor Stephanie Lobdell called the patron saint of Advent. He’s not someone many of us think about with Christmas, but he’s the one whom Mark first affirms as Isaiah’s “voice crying out in the wilderness” to “Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight”:

John the baptizer appeared in the wilderness, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. And people from the whole Judean countryside and all the people of Jerusalem were going out to him, and were baptized by him in the river Jordan, confessing their sins.

Now John was clothed with camel's hair, with a leather belt around his waist, and he ate locusts and wild honey. He proclaimed, "The one who is more powerful than I is coming after me; I am not worthy to stoop down and untie the thong of his sandals. I have baptized you with water; but he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit."

Mark 1:4-8

John is not the One, just the one who tells us of the One. That One will, according to Matthew and Luke, come to baptize the world with the Holy Spirit and fire. And he’ll have plenty of kindling.

John is one of my favorite figures in Scripture, partly because he is a guy who seems to have triple-dipped his fire rations. From his clothes to his diet, he’s ablaze. So much so that I often wonder how many in the Christian church would actually want to hang out with him.

But maybe that’s wrong. Scripture tells us John was very, very popular. He was charismatic in the original sense of the word: gifted. And everyone knew it. Many in power feared it, yet still came to him seeking his baptism, for many mistook him as The Fire. His moxy gave him a following without trying or caring, the Rick Rubin of the Jordan river (who, btw, makes great points about art that I wish more Christians pondered).

Maybe, then, it’s not whether we would identify John as a holy man, but how many of us would mistake John for Jesus, like so many did in his time. We unconsciously misidentify charismatic people all the time as wielders of The Fire. We do this with all forms of spiritually powerful people, leaders who know how to cultivate an image and be smooth social operators.

We can forget that the most holy part about John is his ability to recognize that he was not holy. He was not The Fire, just a guy who knows The Fire when he sees it.

My time as a flamethrower

But do we know it when we see it?

Most of us can feel its warmth, or maybe see some sparks, or trails of smoke. We certainly see the fires of our passion. We then sometimes think The Fire can be identified as dancing, music, sports, personal expression, and finding our authentic selves…much less our vices, those extra salient, dark matter anti-fires.

At least that’s how I was early twenties. I had long fallen out of anything to do with Jesus, but was still a spiritual seeker. Emphasis on spirit: I didn’t believe in a God to seek, so I self-defined spirit and sought myself. I got a tattoo of my home state’s motto, esse quam videri, “to be rather than to seem,” and dedicated myself to being more authentic. In a heroic display of deep narcissism, I moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in comedy. I had never felt more alive than working my crappy mailroom job at a payroll company, driving my red ‘97 Tercel to open mics all over LA. I learned a lot about myself, about failure, about all the side street shortcuts to make the next signup, about which rooms required talking over a blender, and about the utter depression the life of a struggling, self-involved career.

And yet in all that, I felt on fire. I stayed on fire by pivoting from that wrong lane, I tried new things, I opened myself up more to conversations instead of monologues, and my artistic pursuits took about 30 turns I didn’t expect. I chose my own religion (with a podcast no less), even writing something of an unpublished memoir about my church shopping through every spiritual community East and West, and eventually fell into an ayahuasca group, which eventually brought me to the doorstep of divinity school, another place I could self-define and self-refine.

The whole time I never felt like I needed God; I already had fire. And I was sure the divine pursuit of the authentic self was The Fire; the worship of my own spirit.

I don’t want to pretend like there was nothing good and nothing of God in all those years. While there is something of The Fire in our pursuits and any other passion, they are only—merely—fires. Often perfectly good fires. But a classic formulation of idolatry is when we make a fire into The Fire. We then think the Fire of God is ours to kindle and burn whatever, or whoever, we want.

Many would-be John the Baptists have thought the same thing. We all know charlatans of many stripes, and some of us have even played one for a time. Far from a new thing, the book of Acts tells us about preachers like Simon the Magician who grew a messianic cult and kinda founded Gnosticism. In contrast to them, John says, “Don’t look at me; I’m just gathering wood and building the pit.”

The Taming of John and the Death of Protestantism

As much as I love him, meditating on John the Baptist often makes me sad, because he reminds me of my younger, more fiery years. As a spiritual psychonaut, I once felt close solidarity with him. I felt like I was with a group of Christians who were all collectively Johnny Baptist on the bleeding edge of our religion, helping build its future, and pushing the Church into the next century. But I saw how those fires burn people, sometimes severely, and how they burned me.

And while I love the Presbyterian congregation I just began serving in rural Vermont, we’re small, much smaller than we were for centuries of Scottish-descended farmers. We love each other, love who we are, and love where we are, but we sometimes find ourselves in a Western Civilization-sized pew, asking ourselves about the Church’s role in society and our relationship to God: where is the Fire?

Indeed, I had a (thankfully rare) crossover event between Twitter and real life this week. Anglican priest Ben Crosby wrote a piece for Plough, “Zero Episcopalians,” that was shared with me by my retired pastor dad and his friends. In it, Crosby laments the collapse of mainline Protestantism in a way that resonated with me. For those hoping I have a solution to this problem, I’m afraid I am yet another guy with a newsletter who can only just ask questions. But without putting words in his mouth, I can hear Crosby and my dad’s friends asking this same Advent question in similar words.

I never was, and still am not, John the Baptist. But even though I’ve ditched the blotter paper and the setlists of half-baked jokes, it saddens me to consider that I don’t know what church would hire John the Baptist—the man of the wilderness—and honor the part of him that must stay in the wilderness. Even in dying denominations, I think the mores of polite Christianity would suffocate him. Even in the comparatively wilder evangelical, Pentecostal, and otherwise charismatic branches of Christianity, John wouldn’t last as a mangy almost-outsider. Nobody really wants a John unless they can tame him.

As Richard Rohr says, the prophet is on “the edge of the inside.” They still honor the tribe, love the tribe, respect the tribe, and are still in the tribe…but barely. John is perhaps the paradigm of this. He’s still Jewish—even keeping kosher with locust-honey sandwiches by the fistful—but in an outsider way.

In many ways, John is a vital model of what the Church should be about: in the world but not of it; part of the culture, but just barely inside it. A little bit different. A little bit wild. A little bit untamed. In the Reformed tradition, we sometimes unconsciously mistake “Reformed” for being “tamed by the world” instead of “shaped by God.” Conversely, we may think that being Reformed means it is our job to reform the Church in our image, and we play with matches in the process.

And so part of the challenge of our mission is to do what we can to keep being a pit for The Fire without thinking The Fire is ours to wield. Because if it’s a fire we can control, it’s not the Fire of God.

Inbreaking and Indwelling

Christmas is a celebration of what professor Andrew Root of Luther Seminary calls “the inbreaking” of God in our world: the God who is not us, who is outside of us and our world, coming into our world. Advent is a special time, but it’s also just a special emphasis on what’s always happening. In the birth of Christ, we see the epitome of how God breaks into the world to dwell within it. But God is breaking into the world all the time.

Mysticism is often a dirty word for Protestants. Earlier this week, Presbyterian scholar Lydia Griffiths talked about how contrary to (our own) popular belief, mysticism fits perfectly well in our tradition. But from my earlier travels, I also know how mysticism without God—Dr. Root’s special—can easily become self-worship. In cultivating an inner, contemplative life with God, we must always be waiting for, praying for, and looking not to exalt our inner stirrings as God, but for the Fire that both comes from outside yet also dwells within us (hence Indwelling). Because even more than John the Baptist, the Holy Spirit is an outsider who chooses to become an insider—yes, like Jesus Christ.

In my own reconversion experience, I felt an inbreaking of God that I could barely put into words. Maybe you have had similar life-changing, inbreaking experiences, moments where Someone interrupted your narrative and wove you into a bigger story. Maybe you tried your hardest to recreate that experience, to recapture The Fire, or create it for someone else. I don’t know about you, but over time, it became clear to me that I could not manipulate yesterday’s inbreaking or else it wouldn’t be inbreaking—it’d be self-making. We have to trust The Fire is coming enough to avoid that.

Tending

Again, there are so many Advent questions to choose from. In absence of idol-building, “what to do” is always there; “how” is always there. How do we keep the Fire alive? How do we witness it? How do we not mistake it for our fires of passions? Or like in Peter’s letter, how should we live while we wait for the Fire?

If God kindled the fire, how do we make ourselves into a wick for God’s flame?

Maybe it has something to do with the perpetual pivoting of repenting, “turning back,” telling the truth to release its tyranny, emptying ourselves of what gets between us and God. After all, John was a dude whose emphasis on preparation for God’s coming could make bunker owners seem carefree, and his preparing baptism was all about forgiveness for the repentance of sins.

But repentance by itself doesn’t save. John knew it; he knew his baptism was about cleansing, a Jewish purification ritual, a renewal of love in the language of his fellow insiders. Christ’s baptism—again, done with the Holy Spirit and fire—was a new covenant with an old God, an outsider becoming an insider to welcome outsiders back to a new inside.

The Fire was given to all of us, sealed in the sign of baptism. The Fire was given to you from creation, even when the journey of discipleship can be like walking with a candle in a rainstorm. But no matter how the drops tumble, how you feel this week, this year, this decade, or longer…no matter how much the small fires of our passions flicker, you can never lose The Fire.

Sometimes to know it, we need to be still—very, very still—to let all the little fires die down. We can trust God enough to know that he is always kindling the Fire, that it never dies away, for Christ is the Fire of God.

We can remember this in our darkest night, the coldest days, the bleakest wilderness, when we’re crying out, “Where is your Fire, O God?” It lives in you. He always will.