The Living Image

Who Zaccheus saw

Jesus entered Jericho and was passing through it. A man was there named Zacchaeus; he was a chief tax collector and was rich. He was trying to see who Jesus was, but on account of the crowd he could not, because he was short in stature. So he ran ahead and climbed a sycamore tree to see him, because he was going to pass that way. When Jesus came to the place, he looked up and said to him, “Zacchaeus, hurry and come down, for I must stay at your house today.” So he hurried down and was happy to welcome him. All who saw it began to grumble and said, “He has gone to be the guest of one who is a sinner.” Zacchaeus stood there and said to the Lord, “Look, half of my possessions, Lord, I will give to the poor, and if I have defrauded anyone of anything, I will pay back four times as much.” Then Jesus said to him, “Today salvation has come to this house, because he, too, is a son of Abraham. For the Son of Man came to seek out and to save the lost.”

Luke 19:1-10

This week, we have a story about a man who needed to see.

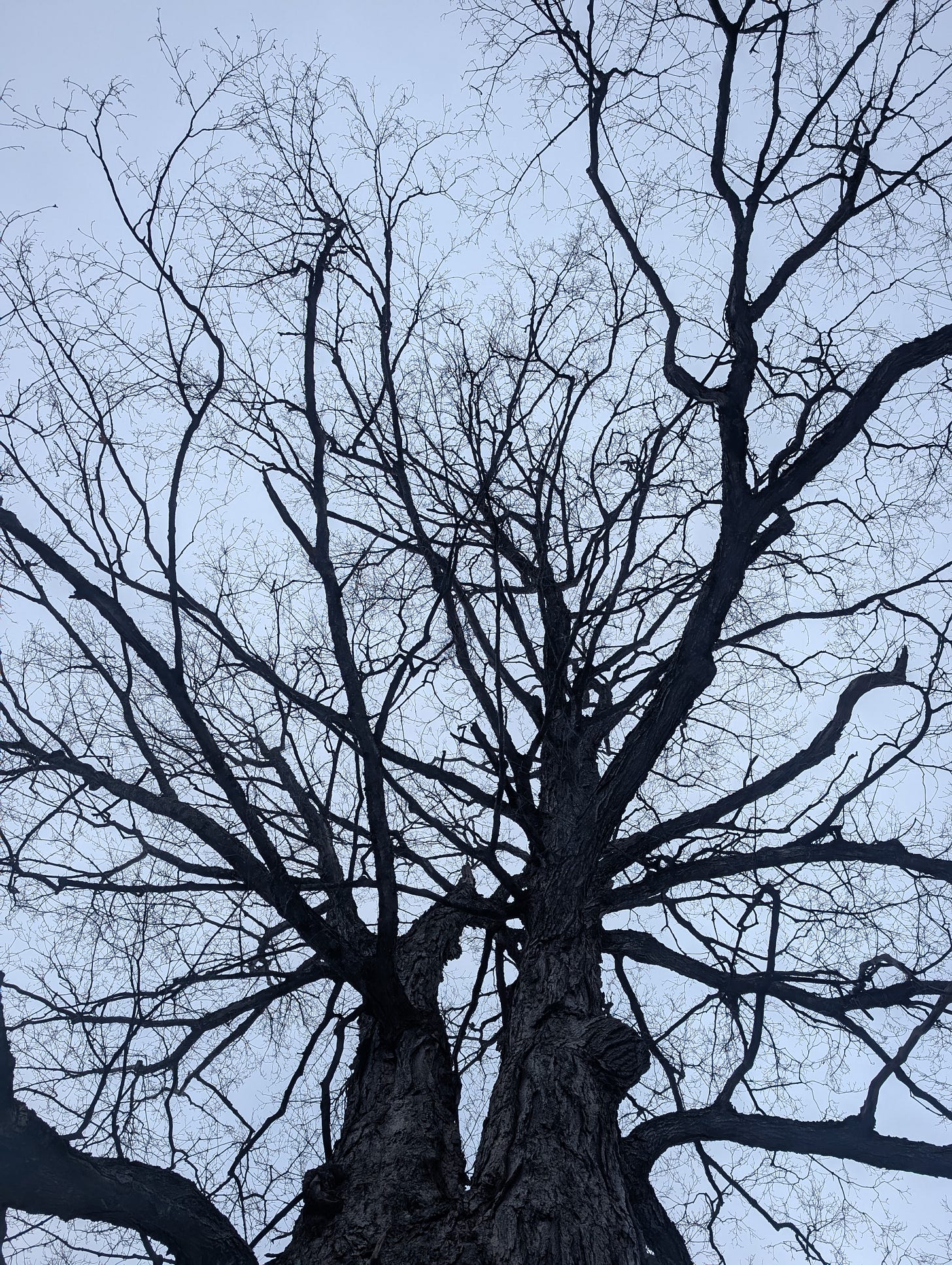

I wonder if Zacchaeus might have had an image in his head of a good life. Wealth, prosperity, fine dining, the things that being a tax collector could help. Skim off the top, pad the bottom line. Of course, however real those luxuries were, they were ultimately false images of goodness. It was not until he saw Jesus that he saw the better image of the good life: generosity, charity, and forgiveness of debts instead of collecting them.

But he hadn’t yet seen Jesus. He had just heard rumors about him. He probably had some true and false ideas about him. But something in him just knew he had to see him. And he did.

When we read Scripture, we encounter lasting, piercing images of Jesus, direct encounters people had with Jesus, preserving them so that we might see him in the image. These images were not simply trying to recount a set of facts, but point beyond the image of Christ, who himself is the image of the invisible God (Col 1:15), pointing to his love. The image evokes not only lessons taught, but how it felt to be there.

You can imagine Zacchaeus telling the story later to his friends. “I couldn’t see him, there was this big crowd, but something in me knew I had to see him…so yeah, I climbed a tree.” He didn’t know why his heart burned, and we don’t know that he ever saw him again. But seeing him changed his life. Of course, as Jesus tells Thomas, “Blessed are those who have faith and have not seen.” (John 20:29) But also, bless those who only see for an instant, who know Jesus for an afternoon, and then he’s gone. And they’re left with a living memory.

While I want to focus on images and visions, it’s important to note that we are not to deify them. Christ doesn’t say to Zacchaeus, “Zacchaeus, I’m gonna blow your mind today. I’m gonna show you the most incredible sights you’ve ever seen, it’ll be awesome.” No. He just invites him to a meal: “Let’s sit down together.” He still invites us all to a simple meal, bread and cup. He tells us, “I’m here when you eat this.” He tells us, “I’m there when you break bread with your friends,” gathered in his name, that is, his character, his essence.

I can’t say all the reasons why Jesus does this. But I think he knows that meals are concrete. You are either fed or not. But, and it’s hardly novel to say, images can be false. Images can lie to us. We all know looks and covers of books can be deceiving. We now have AI capable of completely fabricating realistic forgeries from a couple of lines of text.

In our Estuary discussion group this week, someone brought up this car that their father had left behind when he passed away.1 It was a Dodge Omni that was more than a Dodge Omni. I mean, it wasn’t much itself. His dad hadn’t driven it in decades as it sat in the garage. But when he passed, there was a passionate fight over who it was supposed to go to. Finally, one grandchild got it. And then as soon as they took it on the road, it died almost immediately because the engine was busted.

In chewing on this, our Quaker friend Stark pointed out something we’ve all seen: when we die, what we leave behind us immediately becomes symbolic. The car or the farm is more than a car or a farm, but dad’s car, mom’s farm. And it’s true, what we leave behind isn’t just the thing, but what that thing points to—in their case, their love. The most powerful photos that have ever been taken are more than just what they show, but what they represent: how incredibly small we are in the universe, the desperation of poverty, the risks of immigration, the horrors of war, the joy in finally finding peace.

We need images. Not photos, images. The gospels don’t give us photos, but images. Hope takes the shape of an image, for we can only run so far running away from something. We need to find something that draws us, something to aspire to, a picture of what is possible. We can’t run forever on an anti-vision, on being against something, even if we are right to be against it; Jesus did not simply denounce the world as it was, he told us about the kingdom of God. He did so through the farming parables, stories, sheep and goats, coins, brothers, seeds, wheat. Real things we could touch, not only see, just as his flesh was something we could touch, not only see.

But in the awful predicament that is our sin, false images can draw us almost as captivatingly as true images. Sometimes, we are drawn to a false image of the future: if only everybody would just X/Y/Z, the world would be perfect. Sometimes, the false image is an idealized past—if only we could be as perfect as we imagine things were, that’s a vision we can follow.

Sometimes I feel like what is happening in the country is like we have all lost whole generations of saints who left us this car. It used to work pretty well, but now when you try to drive it, it breaks down. Sometimes you gotta wonder if people are intentionally trying to total it to cash in the insurance claims. But at any rate, nobody remembers how it all fully works anymore. So we fight over the car, because it’s more than a car, it’s an image of a country we all inherited that is neither completely true nor completely false, neither fully good nor fully evil. (But it does seem like it used to work.)

For us Christians, the Church is another car we’ve inherited. In our nostalgia, we sometimes imagine it as something more perfect than it really was, while the New Testament actually preserves just exactly how imperfect it’s always been. Read the Epistles start to finish, and you will not only hear the inspiring words that we read in worship, but also the fighting, the false teachers, the unethical behavior, the pride, the confusion. If we are holding onto an image of the Church we grew up with from all the wonderful saints we are remembering today,2 and if we think if we could only bring it back, it would be perfect peace and harmony, we may be forgetting a few things. Yet we also know that the Church is worth holding onto because it is Christ’s body; more than an image, it is actually real. You can touch it, because it is made of people. And when we actually (forgive me) let “Jesus take the wheel,” we can still do many great things with the Church that we can’t do by ourselves.

The thing about false images is that we eventually get betrayed by them, even as we struggle to let them go. Ask me how I know. Maybe it is more comforting to pursue a false vision than to realize we can’t see clearly by ourselves. The impossible situation of our sin is that while we can’t see clearly ourselves, we still need images.

But the good news of the gospel is we don’t have to see by ourselves. We have the image of the invisible God in the real person of Jesus Christ. He is not nostalgia, but a living memory of a true image. He is a true vision that cannot simply be let go, and he will not let you go. He did not let the scandalous Zacchaeus go, and as tradition goes, Zacchaeus would eventually become the first bishop of Caesarea. Just seeing Jesus for one afternoon changed his life. He was as real as the saints were in your life. As real as the love from them that you know wasn’t theoretical, wasn’t abstract, wasn’t a political project, but was so real you could feel their touch.

Many theologians believe the Zacchaeus story captures the gospel in 10 verses. A man lost in the crowd and hated by the crowd if they knew who he was and what he’d done, lost to himself and doesn’t know what good is, and then one day he yearns before he even knows why he’s yearning that he needs to see the One who is good, who calls him by name, honors him, and says, “I’m going to eat with you today.” It is not only Zacchaeus, but us, through this sinner, who can see a living Christ.

Maybe you still can’t fully explain to your friends why Christianity, why Jesus. Maybe you can’t fully explain to yourself why. And yet, there’s something, there’s something about the image of him that speaks to his even deeper reality. And when we see him, we fellow Zacchaeuses, we know we must walk with a different kind of vision: by faith, not by sight, (2 Cor 5:7). The vision of faith does not see what is invisible yet trusts it. But the vision of the invisible is grounded in the visible Jesus.

For Jesus did leave us a few things we call sacraments, “visible signs of invisible Grace.” He does not only leave us the mysterious Holy Spirit, but some really simple signs. They aren’t fancy. They’re not elaborate visions that can deceive. They are elemental: bread, wine, water. Because while we need images, we need more than images—we need the real thing, the substance. Gnostic Christians had plenty of visions. Elaborate visions of inner worlds and outer worlds. But they were not so grounded in what was material, the simple, the true.

When Jesus gives us these simple things, he invites us to eat, and “Do this in remembrance of me.” Just as Zacchaeus remembered that day forever. Just as they all did. “Remember me,” he says. And what is amazing about this memory of Jesus is that he is not a relic of the past, but a living memory. He is here. He is still alive. He is the risen Lord. Amen.

Shared with permission but anonymized

This sermon was delivered in celebration of All Saints Day, but on Sunday