Testing Our Scriptural Guts

Reading scripture beyond our instincts

Transfiguration Sunday

Because I have the week off from preaching, I’m going to break from my normal posts to peel back the curtain a bit. I thought it might be interesting for some readers to hear how at least one preacher thinks through scholarly commentary in their sermon prep, using some thoughts from a course on Mark that I took with Prof. Larry Wills.

The text we’re working with is a somewhat strange story, Mark’s depiction of the momentous Transfiguration. The Transfiguration is given its own liturgical day in most denominations, coming right before Ash Wednesday in the Revised Common Lectionary. Many see it as the symbolic (and physical) apex of Jesus’ ministry, which then precedes Jesus’ journey and descent into his last days in Jerusalem:

Six days later, Jesus took with him Peter and James and John and led them up a high mountain apart, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his clothes became dazzling bright, such as no one on earth could brighten them. And there appeared to them Elijah with Moses, who were talking with Jesus. Then Peter said to Jesus, “Rabbi, it is good for us to be here; let us set up three tents: one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” He did not know what to say, for they were terrified. Then a cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud there came a voice, “This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him!” Suddenly when they looked around, they saw no one with them any more, but only Jesus.

Mark 9:2-8

Even in Mark’s famously short and sweet style, there are a million potential sermons in these seven little verses, and they have all been preached. But before I focus on the passage, let’s start with a higher-level view of scholarly engagement with scripture.

Some Commentary on Commentaries

Not every preacher in the world believes in sermon preparation at all, some believing you should just start talking and let the Spirit lead. But in the Reformed tradition, part of how we think about the Spirit’s leadership is how it leads us in discernment, in this case through engaging what people before us have said. After all, there are literally thousands of years of thought into every passage in the Bible. It would be hard to overestimate just how many millions of hours of thought, from both secular and religious perspectives, have been poured into the meaning of just one chapter. This can be a humbling and intimidating realization when one is trying to find something both new and accurate to say (though novelty can be overrated anyway). But in another light, it’s also an exciting opportunity for any Scripture reader to be in communion with all the readers across time and space who came to these same words for understanding.

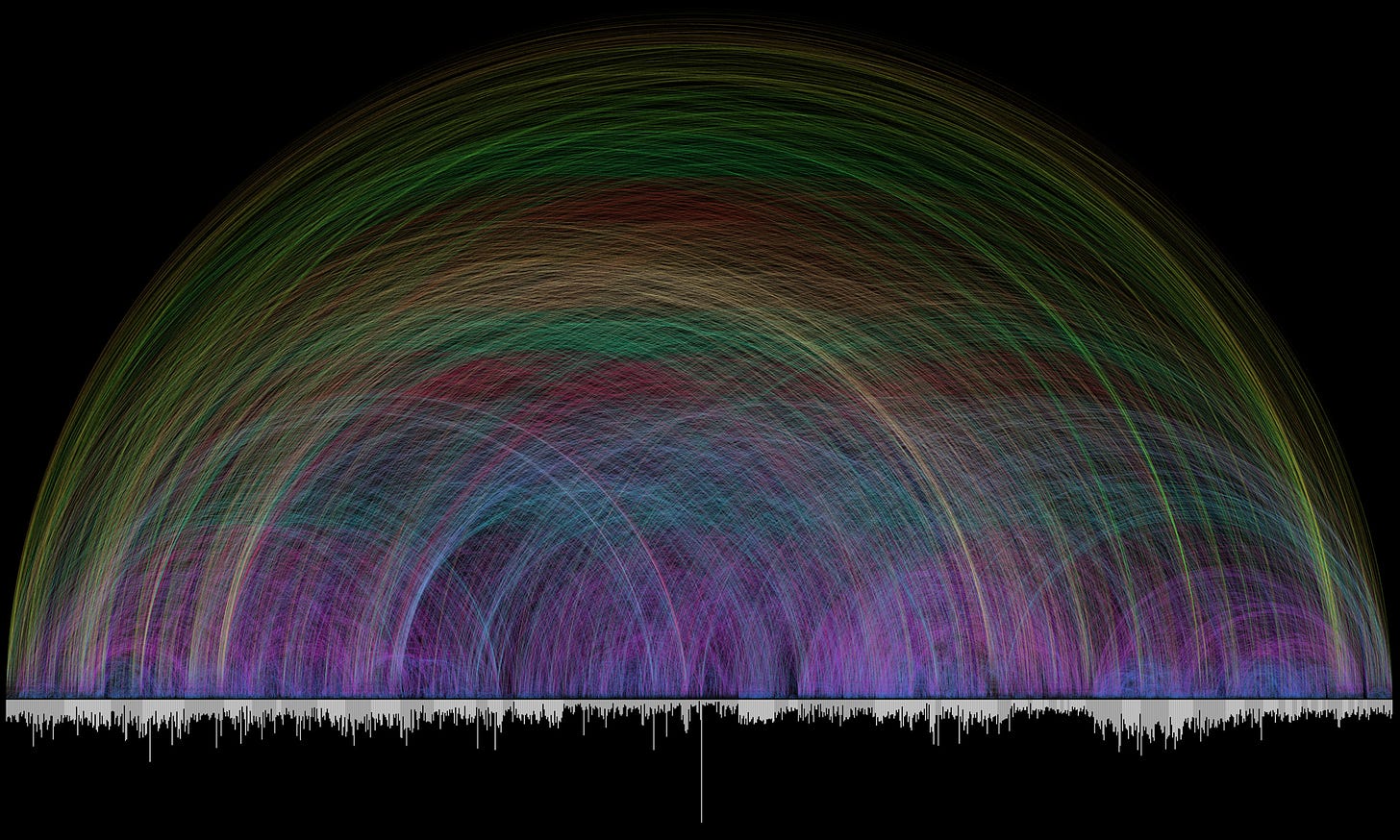

Part of the complexity involved is that, as many have noted in sharing the following image, the Bible is deeply intertextual. This graph by Chris Harrison has been shared a lot in recent years, showing all the cross references the Bible makes to itself:

The implications are staggering. Any given story does not have a meaning, but many meanings—though not all interpretations are created equal. At minimum, this makes the Bible an endless literary quilt that can be meaningful no matter what one’s theism may be. Professors like Andrew Teeter teach how to read the Bible as literature in a way anybody from devout, traditional believers to modernist atheists could learn to see part of what Scripture is “doing.” In my experience, reading the Bible as literature (just one lens of many) does not make it any less the Word.

Given its unfathomable complexity, we who are charged with having things to say about The Book look in part to scholarly commentaries, which are their own dense labyrinths of hyperlinked texts. Such commentaries are made by scholars from all kinds of religious commitments, including those with none at all.

For those who are not used to it, sometimes the process of hearing how scholars engage the Bible as part literature, part history, part sociology, part everything can feel like it diminishes the Bible’s divine inspiration. For example, if Mark’s gospel is in a genre that seems to be a product of its time, which Matthew and Luke appear to have heavily borrowed from, some may feel like it takes the Holy Spirit out of the equation and makes Scripture feel artificial and man-made. To me, nothing feels further from the truth, no more than learning biology or physics diminishes the creation. It is just trying to be more intimately in communion with the Spirit in grasping for the specifics of its movement.

Further, engaging in scholarly commentaries—or any other discussion of Scripture’s original context—does not lock us into a single meaning in one time and place. Knowing more of what Mark might have been gesturing to his audience at the time is important, but part of taking the Bible as truly divinely inspired is the belief that God still speaks through the Scripture to our time as our human context changes. We ought to study and search for what Scripture might have meant to its earliest audiences, and Christians ought to faithfully witness to how we refract all of it through the light of Christ, but we also ought to remember that we will never learn it all or exhaust Scripture of meaning, and we ought to let it speak to us and shape us in different ways. This isn’t trying to slide into pure relativism. There are, I believe, “wrong answers.” But there are also many, many theologically sound ones.

The Vital Zone and the Danger Zone: Testing “What Speaks to Me”

Alas, we are finite creatures who can barely do times tables in our heads. We can never speak to all the meanings of Scripture even if we could know them. Jesus Christ himself is, in part, God’s attempt to relate to us in our finitude. And so, in reading all these words about him and his life—and the many more words written about these words—you often have to zero in on one thing at a time. And when I am trying to figure out what things to say about Scripture to help make it feel alive for someone else, I have to start with what feels alive to me. This is what I’m going to make up on the spot right now and call the Vital Zone of Scripture.

So, let’s go back to our Transfiguration text. While there are plenty of layers to unravel about the meaning of this story about Jesus, what has often struck me most about this story is Peter’s reaction: “Then Peter said to Jesus, ‘Rabbi, it is good for us to be here; let us set up three tents: one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.’ He did not know what to say, for they were terrified.” (Mark 9:5-6)

When Jesus is doing some pretty crazy stuff, like suddenly having clothes that burst so bright that “no one on earth could brighten them,” not even Billy Mays, it’s sometimes easier for me to relate to Peter. This is because Peter is often our model of How to Not Disciple Real Good, our funhouse mirror. So, thinking about Peter in this text is right in my Vital Zone.

It is here that I and many a preacher fumble from the Vital Zone to the Danger Zone. This is the point where we take what leapt at us in the text, move straight to an interpretation, then deem our interpretation “divine inspiration,” and get to work finding reasons to justify ourselves. This is just a reformulation of a classic pitfall: the risk of doing “eisegesis” instead of our goal of “exegesis.”

Exegesis, reading out of the text what it says and having it shape us and what we witness to, is where we want to end up from the Vital Zone. Eisegesis, which is reading into the text so that we make it mean what we want, is the Danger Zone. They both come from a living place within us. The risk comes in chasing our desires rather than opening ourselves up to be changed by the Spirit which often defies our impulses. As Nick Hornby writes in High Fidelity, “I've been thinking with my guts since I was fourteen years old, and frankly speaking, between you and me, I have come to the conclusion that my guts have shit for brains.”

My Vitally Dangerous Zone here: whenever I’ve read this in recent years, my gut instinct was that the lesson behind Peter’s clumsy discipleship is that Peter wants to “put Jesus in a box,” to keep him secure, to make a reliable worship spot for pilgrimage, and so our takeaway lesson is that Jesus cannot be boxed in like that.

I mean, that still feels nice to me. It’s not really wrong theologically. But is this theological impulse what this text is actually getting at? Or is there something else going on?

If I don’t examine it, the Danger Zone can quickly get me far afield from the true heart of the text and more into just how I feel about things. And that might be fine in some contexts. I get to feel things. It’s just not the job at hand. Part of the job at hand is not just to find what feels alive for me, but to let the Word shape me and share it in a way that others might also be shaped by it.

So, in checking my instincts from my Vital Zone, I might use a variety of tools. I might look at the original Greek directly myself, I might check out how the story is portrayed by other gospels to notice any differences in details (for example, Luke’s versions clarifies that Peter “didn’t know what was saying” as if he was fumbling with his words in awe-struck fear). I also might start with other solid theological assumptions to ask more questions: okay, I know Peter is likely somehow in a well-intentioned wrong here, so what exactly is he wrong about? And if he is wrong, why isn’t he rebuked or chastised like he normally is by Jesus when he’s wrong?

So to really find something worth witnessing that isn’t just sharing our best gut feelings, we sometimes have to zoom in even further.

Transfiguration Tents

In this case, I’m going to focus on the three “skenas” (σκηνάς), tents or tabernacles, that Peter wishes to build, one for each holy figure (Moses, Elijah, Jesus). I sampled three different scholarly takes to answer, “What’s wrong with Peter? And why isn’t he rebuked?”

While Delbert Burkett argues Peter’s primary error is mistaking identity,1 Randall Otto argues that Peter desired to build the tabernacles out of fear of encountering the direct glory of God.2 To Adele Yarbro Collins, this response of terror is partially appropriate. But in light of Otto and the rest of Mark, I believe the reason why Peter is not rebuked is that the story is not teaching us as much about Peter, but is primarily teaching us that Jesus as God’s son is a new and unique divine mediator.

The Transfiguration deliberately points to passages from the Old Testament, most directly from Exodus 25:1—31:18, in which the divine speech is also concerned with the construction of the “tent” or “tabernacle” in the wilderness.3 To Burkett, Peter's error is conflating Jesus with the Hebrew prophets as equals. “Peter mistakenly puts Jesus on the same level as Moses and Elijah by offering to make a tabernacle for each of the three,” he writes, “By putting Jesus on their level, Peter reveals that he regards Jesus not as a preexistent divine being but as a human being who has just undergone a transformation.”4 While this is not directly rebuked harshly, Burkett argues that God’s injection to listen to his beloved son is a key clarifying mark to Peter’s error.

Collins argues that Mark’s version of the Transfiguration indicates a Greco-Roman influence in which “an account of an epiphany is often associated with the foundation of a cult or a festival. Peter is proposing that the triple epiphany be commemorated at least by the building of a shrine and perhaps by some regular ritual observance.”5 But if this is a well-intentioned theological error, it is not rebuked as it is elsewhere in Mark, including in Mark 8:33 when Peter is associated with Satan. Collins believes that there is no rebuke because he “express[es] the typical and appropriate human response of awe, reverence, and terror to the manifestation of divinity.”6

But given Jesus’ words in Mark 5:36 and 6:50 to “not be afraid,” is Peter’s terror really endorsed by this story?

I do not think so. Instead, I am most compelled by Otto, who also argues against the interpretations that Peter wants to establish a new cult:

A fuller appreciation of the overwhelming power of the divine glory will bring with it a better understanding of Peter's comment regarding building τρεις σκηνάς, [three tents]. It will dispel the idea that the disciples “desire to linger and to bask in the ease and reflection of this glory.” Such assertions defy the way biblical and extra-biblical literature regularly portray those confronted by the presence of the divine glory, either in person or in a vision. There is no ease in the presence of such glory and no desire to linger or bask in the presence of such a consuming radiance. There is only fear, anxiety and distress. Peter sought to relieve this distress and remain alive in making the suggestion about building τρεις σκηνάς, tents or tabernacles whereby the divine glory would be veiled from destroying the sinners they knew themselves to be.7

In this light, Peter’s desire to build the tents is not “to put Jesus in a box,” but born of a holy fear, a fear is both appropriate and inappropriate at once. On the one hand, it is appropriate with everything his tradition has taught him about the presence of God. And yet Mark’s depiction of Jesus, the divine Son of Man and Son of God, is as a new category of divine being. While the words “do not be afraid” are not uttered as they are in other gospel narratives, the implication that Peter is wrong to want to build tabernacles suggests his fear is still misplaced. This is perhaps because Jesus represents God’s symbolic action in the world, that God has sent a special mediator who not only wants us to not fear his presence, but actively seeks us out.

Putting it all together

I’m not going to stand here before you and God and pretend I do this much research before everything I write. I’m usually making quick mental notes and outlines rather than sharing all the details. Ain’t none of us have time for that all the time. I'm also not going to pretend I always avoid the Danger Zone.

But I hope reading this was a helpful model of one way we can move through our first gut reading of a text into discovery. While I used to think of this as an example of Peter wanting to box Jesus in and hold onto him, to put him on a mountaintop, that doesn’t really feel faithful to what the text is saying, even if it’s not exactly wrong. Again, I very much do believe that, and I don’t think the text refutes that as a potential broader theme throughout the Bible, but it just doesn’t seem to be talking about that here.

Primarily, this text seems to be teaching us something about Jesus more than Peter. And in teaching us something about Jesus, Mark points to a new unfolding aspect of God’s life in our world, including through the life of the mind.

So if I were to have to preach something on this text, instead of focusing on Peter, I might focus on how Jesus is still very present in the world, in the brilliances none of us can polish. I might say something about how God is still a mediator in our lives if we let him, and he is deeply invested in our humanity, and dazzles us on the mountaintop, meets us in our fears, and guides us out of ourselves. Because sometimes we can trust our scriptural guts, and sometimes we need to test them.

Burkett. (2019). The Transfiguration of Jesus (Mark 9:2-8): Epiphany or Apotheosis? Journal of Biblical Literature, 138(2), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.15699/jbl.1382.2019.542353

Otto. (1997). The fear motivation in Peter's offer to build three tabernacles or booths. The Westminster Theological Journal, 59(1), 101–112.

Collins, Adela Yarbro, and Harold W. Attridge. 2007. Mark: a Commentary. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 417.

Burkett, 418.

Collins, 424.

Collins, 425.

Otto, 111.