I am off from preaching this week, so I am offering the following non-sermonic reflection inspired by our lectionary reading this week.

The most vigorous debate in my life is not over the authenticity of psychedelic spirituality, but with my girlfriend about the following: when you’re driving in a car, are you fundamentally inside or outside? This gets me worked up, confuses me, then I forget about it, then forget which side I’m supposed to be on. She argues the answer is “inside” while I argue “outside,” which makes sense, because “outside” is the correct answer. The car itself is outside on the road, and this trumps our relativized nature within the car’s body. If you read no further, please let me know in the comments what side of this you’re on (the right side of history, or “inside”).

This debate has come to mind with the latest flair-up about the insider-outsider nature of Christian. Richard Dawkins, perhaps the world’s most famous and evangelical atheist, recently asserted in an interview that he considers himself a “cultural Christian,” but he’s still glad that there are fewer devout Christians than there used to be.

This conversation is perhaps deceptively perennial; as

has shared, “cultural Christians” go back even to the early Church. It seems to regularly emerges around the big “culturally Christian” holidays, and I last wrote about it with A Doubter’s Guide to Christmas.Of the reactions to Dawkins, one that stood out to me was Esmé Partridge describing Dawkins’ position as “naive”:

Like him, the liberals of the 17th and 18th centuries believed it was possible to renounce the truth claims of Christianity while still upholding its social and cultural mores…Enlightenment thinkers such as Locke and Montesquieu were all, in a sense, ‘cultural Christians’. Yet history has not vindicated their naivety. Without public religion, their legacy has mutated into something very different: anarchic systems of self-interest which undermine the virtues upon which liberalism was originally premised.

In concordance with Partridge on social media, Christians pushed back on Dawkins and others who are openly holding onto the scare quotes of their “Christianity.” It strikes them as both spiritual free-loading and unrealistic—how does Dawkins imagine the beautiful buildings, hymns, and values he appreciates at a distance survive without devout believers?

But I suspect Dawkins holds a position quite common in the West, and perhaps by many in my communities: glad there are still Christians around somewhere, but glad there’s fewer of them who, you know actually believe in Christianity, which they consider to be on aggregate intellectually lacking, bigoted, unhelpful, and literally false even if metaphorically true.

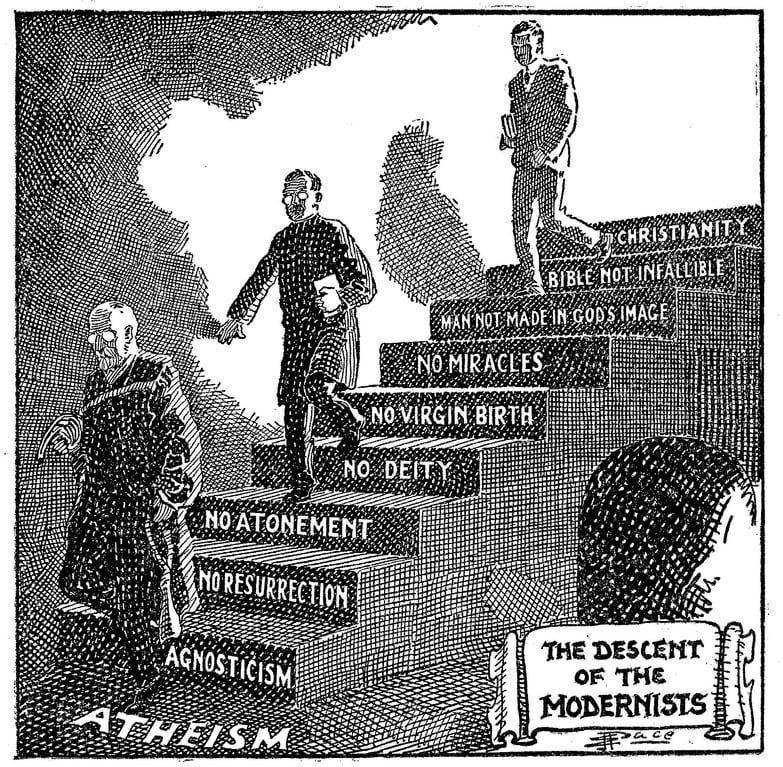

Many Christians have agreed, inspiring generations of religious and post-religious liberals to imagine, “How do we keep the good parts of religion we like without, well, so much religion?”1 And thus mainline liberal churches are at the end of decades (if not centuries) of relaxing standards of orthodoxy for belonging and participation. Many of the early congregations of the Massachusetts Bay colony were founded on independent church covenants rather than credal adherence, leading to schisming tensions in the early 19th century that formed Unitarianism, and with it, Harvard Divinity School. A century later, Harry Emerson Fosdick’s famous “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” was a landmark sermon of 1920s liberal Christianity, contrasted with this also-famous slippery-staircase cartoon published in 1922:

Debates over who is allowed to take communion, credal standards, and acceptable clerical beliefs have resolved through increasing schisms, with splits over same-sex marriage being more a tipping point than precipitating action. Last month, Ed Watson wrote for the

on the state of the tensions in “inclusive Orthodoxy” which elicited a response from last week.In looking at allll this, it strikes me funny that going back to Christianity’s very origins, there is perhaps nothing more “culturally Christian” than debating what kinds of beliefs are authentically Christian. Alongside it, a question that is also just as perennial (which Williams’ work gestures to) is how are confessional Christians to relate to our neighbors who seem to like that we exist but keep themselves at arm’s length?

While maintaining the importance of belief and boundaries around it, I believe the answer is with generosity. I think we get there by appreciating how cultural Christianity might function in relationship to the Church and appreciating how the gifts of intellectual honesty manifest among those who just can’t believe.

The Front Porch of CS Lewis’ House

C.S. Lewis’ most famous work that wasn’t about lion-Christs and redeemable children is Mere Christianity. It bears its title from Lewis’ attempt to describe the most bare-bone essentials of Christianity. In the preface, he likens his work as not attempting to get into doctrinal debates and the juiciest bits of the faith, but as someone describing a hall:

I hope no reader will suppose that ‘mere’ Christianity is here put forward as an alternative to the creeds of the existing communions—as if a man could adopt it in preference to Congregationalism or Greek Orthodoxy or anything else. It is more like a hall out of which doors open into several rooms. If I can bring anyone into that hall I shall have done what I attempted. But it is in the rooms, not in the hall, that there are fires and chairs and meals. The hall is a place to wait in, a place from which to try the various doors, not a place to live in. For that purpose the worst of the rooms (whichever that may be) is, I think, preferable.

It is true that some people may find they have to wait in the hall for a considerable time, while others feel certain almost at once which door they must knock at. I do not know why there is this difference, but I am sure God keeps no one waiting unless He sees that it is good for him to wait. When you do get into your room you will find that the long wait has done you some kind of good which you would not have had otherwise. But you must regard it as waiting, not as camping. You must keep on praying for light: and, of course, even in the hall, you must begin trying to obey the rules which are common to the whole house. And above all you must be asking which door is the true one; not which pleases you best by its paint and panelling. In plain language, the question should never be: ‘Do I like that kind of service?’ but ‘Are these doctrines true: Is holiness here? Does my conscience move me towards this? Is my reluctance to knock at this door due to my pride, or my mere taste, or my personal dislike of this particular door-keeper?’2

If Lewis welcomed people into the hall of the common Christian home, perhaps we should reconsider the relationship of “mere” cultural Christianity to this house. Perhaps we should see cultural Christianity as the place that one must pass through in order to enter the hall at all. In that sense, cultural Christianity is the front porch of this house.

Legendary University of North Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith likened college sports to being the front of the university: the most visible but not the most important part. And cultural Christianity is, indeed, what people see first of Christianity when they pass through the global neighborhood. For some they see something beautiful in its antiquity, others something dilapidated. It is also the place where home-dwellers like to hang out and view the rest of the world from the judgment seat of our favorite rocking chair. And we should all hope that visitors to the porch know it’s not the most important part of the house.

My Time On (and Off) the Porch

I have a soft spot for those outside the Church but who want to hang out and talk on the porch. Born and raised in the tradition, I wanted to never see the Christian house again for many years. It is only because there was a viable front porch and Christians sitting on it, including some teachers whom other true-believing insiders look down on as inadequate and false, that I came back to the faith.

For example, the pastor-turned-author Rob Bell has not produced any work of late that moves the needle for me. And if I were to look back at some of his work that once really inspired me, I may wince a bit at mistaking it as on par with theologians and authors I’ve read since. And yet if it were not for his book What We Talk About When We Talk About God, I may not have even become a Christian again. Forget the porch,I may not have stayed long in the front yard.

At one point, Bell likens God to that which (or Who) moves us spiritually from point A to point B to point C and on, explaining the contextuality of difficult Old Testament passages as showing a God who moves us collectively towards liberation, one step at a time, meeting us where we are in the moment so that we can comprehend him. Looking back, I feel a bit uneasy about equating God as synonymous with cultural progress for how this can be dangerously conflated with equating God with modern political movements as intrinsically divine (hardly a new debate either). But at the same time, his book did move me from rejecting the faith I was raised in towards being curious enough to re-discover it. I found an invitation to the front porch that understood why I wasn’t inside.

Because of my long and weird journey graced by a bunch of different non-Christian communities and subcultures, I know there are many readers of this newsletter who might also feel much more comfortable on this porch. If this is you, maybe you don’t necessarily feel “culturally Christian,” but maybe a post-modern one, or a meta-modern one, or a mystic one in the backyard or atop the roof, or some otherwise non-literal appreciator of Christianity. There are still many others in my Vermont town who put themselves in a similar category: friends and family of the Church, spiritual seekers and lovers of community, but perhaps allergic to the concept of being a “believer,” and uncomfortable with the notion of converting to get there.

Despite this abundance of friends that have walked with me at different points of my life, I can still too easily find myself in Jonah’s trap. Not the trap of the big fish belly in the depths of near-death, but Jonah’s trap of spiritual pride that resists knowing that God’s grace shines on all, especially those who do not yet know him (Jonah 4:2). Jonah expresses our common human hipsterdom—you just don’t get it, I loved God before he was cool!

But when Jonah remembered in deep gratitude for all the work God had done for him, he did what he was tasked to do: show the love of God to people through being the messenger of God’s warning. And his worst fears were indeed confirmed: God loved the people of Ninevah even though they weren’t “culturally Jewish.” While Jonah wanted to be their gatekeeper, God had other plans.

How does God call us to do the same? And rather than judging the non-belief of those leaning on the railings hardly aware of the home behind them, how can we witness the gift inherent in their doubt?

Authenticity and Intellectual Honesty: Gifts of the Doubters

If there was one thing that kept me away from Christianity for years, it was my desire to be intellectually honest. This was my experience with many of my other secular friends. When I interviewed people for a now-defunct podcast, so many of us missed church, but we could not pretend to believe.

This was the story of my undergraduate professor Bart Ehrman, an (in)famous name in Biblical academia. He is a preeminent scholar,an outspoken agnostic-who’s-technically-not-an-atheist, and instigator of many Christian deconstructions during his long tenure as professor. His credibility comes from primarily his chops, but also his personal journey of being a formerly evangelical, fundamentalist Christian. Once he rigorously studied the Bible, he began to find how many holes there were in what he thought he knew.

After taking his courses, I became a typical product of this discipleship, believing that my old Christian house had been built on intellectual sand. I knew I could not believe Christianity on the merits of its rational arguments. While I wish I had learned of more theological options and the thicker debate in Biblical academia around his approach that I came to learn in divinity school, I’m still grateful for his gift of intellectual honesty. I now feel that I have enough other perspectives, experiences, and theological lenses to where I can be an intellectually honest Christian. But this could not be forced. It could not even be my decision.

When I couldn’t believe in Christianity throughout my twenties, I began wondering about how my old faith—better viewed in hindsight as a “preparing faith”—had deformed me into something inauthentic. Now, authenticity may have become something of a cultural idol in recent years, one that I worshipped too, as my esse quam videri tattoo bears witness to (North Carolina’s “to be rather than to seem”). But authenticity itself is a beautiful thing and a beautiful part of what makes a good conversation on Christ’s front porch. Likewise, intellectual honesty is part of the air that blows through the balusters.

Dawkins probably deserves criticism for how he has often conducted himself as an anti-Christian polemicist over the years. Even when I was reading Sam Harris and chuckling in satisfaction at the fools I left behind (God laughs last), I still found Dawkins a bit much. But for whatever lack of faith Dawkins, Harris, and any other evangelical atheists may have, this should not be mistaken for bad faith. They sincerely do not, and cannot, believe in the Christian story. They have also likely heard just about every Christian argument you can think of, and the prospect of arguing them into belief is unlikely to be fruitful.

And this intellectual honesty that manifests as doubt is also part of Christianity — the air on the porch is the same air in the house. Like the porch, it should be seen for what it is: not the endpoint, but a gift. For this is how Christ treats it too.

Apologia for Doubting Thomas

Thomas (who was called the Twin), one of the twelve, was not with them when Jesus came.

So the other disciples told him, "We have seen the Lord." But he said to them, "Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe."

A week later his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them. Although the doors were shut, Jesus came and stood among them and said, "Peace be with you." Then he said to Thomas, "Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe."

Thomas answered him, "My Lord and my God!"

Jesus said to him, "Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe."

John 20:24-29

In this famous gospel passage, Thomas gets a bad wrap with his moniker: he didn’t get the benefit of the other apostles who saw the risen Christ first. Yet when he did express doubt, curiosity, and asked for evidence, Jesus does not reject him. He shows him. Thomas did not demand miracles, but evidence, and Jesus met his pursuit of truth with the truth of his wounds.

It is true that unlike Thomas, and like Ehrman, lots of people have asked for evidence and not come to believe. But it does no Christian any good to judge this doubt, but to first pilgrim with those outside the Church in a shared pursuit of truth.

Many in my community never grew up with the stories of Christianity like I did which made my reconversion easier. Many did not know the highly unusual love from Christians that I felt in contrast to the not-so-greener grass I found elsewhere, which was just as vital in my return. If none of us have seen the risen Lord, so many in the world don’t have the blessing of having the stories baked in their bones or a living example of Christ’s love.

As Lewis said in concluding his hall analogy:

When you have reached your own room, be kind to those who have chosen different doors and to those who are still in the hall. If they are wrong they need your prayers all the more; and if they are your enemies, then you are under orders to pray for them. That is one of the rules common to the whole house.3

If this is true for the hall of “mere Christianity,” it is even more true of the porch of “mere cultural Christianity.” If confessional Christians are stuck with mere cultural Christianity, how might we beautify the front porch to better make people wonder what’s inside?

Perhaps, too, we should recognize there is no singular “cultural Christianity,” just as there are many styles, sizes, and functions of porches: is it wrap-around with or more of a mud room to wipe our boots? Is it on the second story, after one has already traveled through a few halls and rooms and needs to get fresh air? And how porous should this cultural Christian porch be? Should it be open-air to the point where it is practically a deck? Should it be the opposite, closed-in and insulated to where it is a sunroom? Should it be somewhere in-between, screened-in to keep the bugs out but to let the air in?

In turn, when Dawkins et al. talk about cultural Christianity, which culture do they mean? For the Englishman Dawkins, we might assume he feels most fondest of British post-Christianity. But what of Appalachian folk wisdom? What about New England humble Calvinist architecture churches-turned-community centers? What about the much-maligned “strip mall” Protestantism (and its valid theological claims)? What about being able to reliably schedule a trip to the Vatican and check it off a bucket list? What about your grandmother who still says she prays for you even if you don’t believe in prayer?

Partridge is right to point out that these things do not sustain by themselves without genuine spiritual fuel:

Cultural Christianity may seem like a sustainable position for those of a generation which has just about managed to keep the vestiges of tradition intact. But with belief rapidly declining and those beautiful parish churches struggling to survive, it is evidently not sustainable. Like any organism, Christianity must recover its roots, or it will die — a fact of life which, as an evolutionary biologist, Dawkins ought to appreciate.

Indeed, Christianity must not eschew the importance of belief. Even the most beloved museums die if the institutions behind them are no longer viable. The true thing, the vital thing, will always be gatekept by vitality itself. There is no home if people are not really living in it.

But where is vitality in belief, or is belief just the hallway into vitality? Where do its doors lead?

Christ’s response to Thomas suggests that the most vital part of Christianity is not in our belief, but is in his wounds. Lest we mistake the quality of our belief for God himself, we should remember that Jesus calls us to believe not for believing’s sake, but because of how belief is an acceptance of an invitation, the scissors that cut through all that separates us from God to open the gift of life in him.

Like Thomas, Christ meets all of us—even Richard Dawkins—in our intellectual honesty. And he shows his wounds.

Christ showed Thomas how the wounds which killed him have no real power. Christ showed him the scar tissue born of self-sacrificial love that stood standing long after hope had been lost. Christ loved him in his doubts through their friendship, allowing him to not just see for himself, but feel for himself.

I am reminded of my friend Ashley Lande’s upcoming memoir. Ashley shares her long journey through intense atheistic skepticism driven by psychedelicism that resonated strongly with my own journey. Without spoiling anything, the pivotal moments of Ashley’s journey come less through any kind of “should” arguments, and more in the pain that God found her in and saw her through.

If confessing Christians want to be good neighbors on our front porch while giving a glimpse of what life can be like inside, it is showing our gifted skeptic friends our own wounds, letting them see and feel for themselves how God heals it all.

This is often how the “parting of the ways” between Christianity and Judaism has been characterized for centuries as the “spiritual movement of Jesus believers” vs. “religious followers of the Law”, stereotypes that benefits nobody.

Lewis, C. S.. Mere Christianity (C.S. Lewis Signature Classics) (pp. xv-xvi). HarperOne. Kindle Edition.

Ibid.

Have you ever spent the day driving in the car and when you finally got to your destination, needed to get outside after having been cooped up all day? (I don’t know your girlfriend, but I think she’s got you on this point.)

Look, I’m not saying that the car itself is not outside on the road. I’m just saying that anytime you tell me to “get in the car,” I will give you grief.