Either fly as far as you can from men, or, laughing at the world and the men in it, make yourself a fool in many things.

Sayings of the Desert Fathers

For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.

For it is written, "I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart."

For God's foolishness is wiser than human wisdom, and God's weakness is stronger than human strength.

1 Cor 1:18-19, 25

Christ for Dummies and Dummies for Christ

Because Lent is a time of fasting, penitence, self-reflection, it’s often got a very serious, even somber feeling. After all, we begin by meditating on the ashes of our mortality. But as we keep walking through Lent with the Desert Fathers, I am thinking with Paul more about what it means to be one of God’s fools. Here is one old fool from the desert, showing us how death actually can be a laughing matter:

The story is told that one of the elders lay dying in Scete, and the brethren surrounded his bed, dressed him in the shroud, and began to weep. But he opened his eyes and laughed. He laughed another time, and then a third time. When the brethren saw this, they asked him, saying, “Tell us, Father, why you are laughing while we weep?”

He said to them, “I laughed the first time because you fear death. I laughed the second time because you are not ready for death. And the third time I laughed because from labours I go to my rest.”

As soon as he had said this, he closed his eyes in death.1

Sayings of the Desert Fathers

The mind is a funny thing on either side of faith. I was just talking with a friend the other day who has been wrestling with Christianity in an intellectually honest way. I did the same (and hope I still do). The struggle, as the kids say, is real: on the one hand, Christianity’s history of theologians, critics, philosophers, and scientists boasts plenty of intellectual firepower. Of all the library shelves that have ever been, there must be more Christian books than any other genres. These are not, as I used to think, pages of empty sentimentalities that I dismissed before cracking open the books in my non-church days. In fact, one reason I came back to faith was reading the cultural and theological criticism of people like Thomas Merton or Reinhold Niebuhr and found it more penetrating and intellectual than the other intellectual types I had grown more comfortable with. Several friends feel the same.

On the other hand, Christianity can just feel utterly ridiculous in its basic propositions. Even for the faithful it is hard to sometimes not feel the insecurity inherent in the “foolishness of the cross.” I do not imagine Paul speaking in abstraction. I imagine he was treated like an utter moron when talking about Jesus to people as he fashioned their tent, seemingly by Jews and Greeks alike. And when attempting to speak of Christ to people out in the world, many Christians undoubtedly feel the same. We don’t hide our faith simply to be polite or in fear of rejection, but sometimes to prevent the disappointment of the side-eye smirking disbelief at belief.

On the third hand, of course we really are fools. We probably aren’t as bright as we imagine. We are imposters of wisdom. After all, we are humans, and like humans, our coping superiority complexes are rather simple.

On the fourth hand of this multibeast, God makes do with fools.

And so like most of Paul’s letters, our reading today (1 Cor 1:18-25) is trying to teach us not just about the nature of God, but the nature of the Church. Paul’s focus is on our holy foolishness, “the foolishness of our proclamation” of the cross:

For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, God decided through the foolishness of our proclamation, to save those who believe. For Jews demand signs and Greeks desire wisdom, but we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles.

1 Cor 1:21-23

Therefore Christians across the centuries have noted that our call is to be “holy fools.” What does that mean, and how do we do that? It’s certainly not the foolish part that’s the challenge.

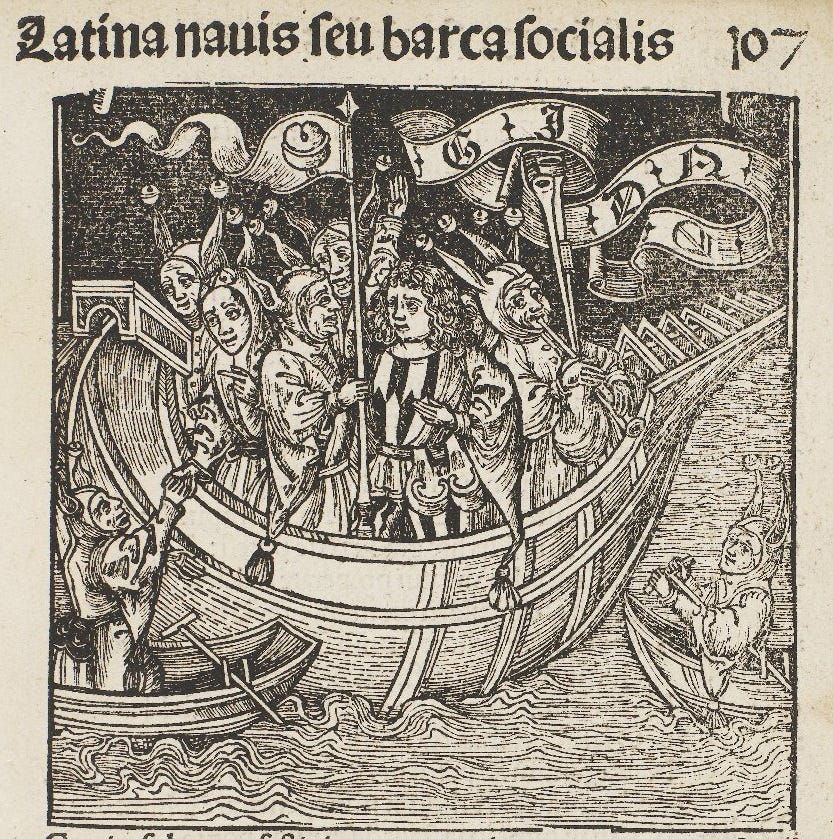

Ship of Fools

Plato once used an allegory called the “Ship of Fools” to represent democracy. Benjamin Jowett’s translation of Plato describes it as such:

There is a captain who is taller and stronger than any of the crew, but he is a little deaf and has a similar infirmity in sight, and his knowledge of navigation is not much better. The sailors are quarrelling with one another about the steering -- every one is of opinion that he has a right to steer, though he has never learned the art of navigation and cannot tell who taught him or when he learned, and will further assert that it cannot be taught, and they are ready to cut in pieces any one who says the contrary. They throng about the captain, begging and praying him to commit the helm to them; and if at any time they do not prevail, but others are preferred to them, they kill the others or throw them overboard…[In such vessels,] how will the true pilot be regarded? Will he not be called by them a prater, a star-gazer, a good-for-nothing?

This perennial human mirror has been used in literature throughout history. Even Robert Hunter, the lyricist for the Grateful Dead, once wrote a song called “Ship of Fools”. Hunter always leaves room for the listener to make meaning, but one rumored interpretation is the song is about how crazy awful the band’s drug-infused world had become both in the band and the subculture around it. Rather than a glorification, Hunter seems to be warning the listener: don’t join this ship of fools!

Back in the Reformation era, some also satirized the Church as a ship of fools. And, well, they were right. The temple of the living God, the bride of Christ, the body of Christ. It is all those things. But it is also a ship of fools.

The Church has always used the analogy of a ship. Cathedrals were built to remind the faithful of Noah’s Ark and a covenantal life in God. But way before that, the New Testament stories of Jesus in the boat with the disciples were understood as an early analogy of the Church. It rides the waves of the spiritual life, panicking in the storm until Jesus calms down the waves. Combined with Paul’s call to foolishness and the brokenness of the Church’s sinfulness since those first-century fights, the only question is whether this ship has had the right kind or the wrong kind of fools.

In the best ways, we can be fools like how Paul means it—holding onto God’s wisdom that looks so foolish to the world. But almost all of us know people hurt by the Church making choices like, well, a bunch of idiots. And these choices sometimes were made by being closely aligned with the world’s wisdom at the time. And sometimes these choices were being too sure we possessed God’s wisdom.

Earlier this week, I appreciated

’s call for us to read the story of Jesus’ anger in the temple in the spirit of repentance rather than our preference for self-justifying anger, looking for the wolves within us rather than just on the outside. We might read Jesus overturning the tables in the temple as overturning the wrong kind of foolishness happening in his Body, which isn’t just our enemies, but in us:Making a whip of cords, he drove all of them out of the temple, both the sheep and the cattle. He also poured out the coins of the money changers and overturned their tables. He told those who were selling the doves, "Take these things out of here! Stop making my Father's house a marketplace!"

John 2:19

For a guy who suffered a lot of things willingly, he didn’t suffer these fools gladly. What would Jesus smash in the Church’s temple today?

And instead of a harmful ship of fools, what does it mean for the Church to repent and return to its port as a ship of Holy Fools?

A Better Ship: Desert Fools and Clowning on Hate

Going back to the Desert Fathers, one of the greatest Holy Fools among them was Abbot Moses, who we see in these two stories:

[A judge was trying to find Abbot Moses,] asking an elder, “Tell us, where is the cell of Abbot Moses?” The elder replied: “What do you want with him? The man is a fool and a heretic!” The judge went on and came to the church of Scete and said to the clerics: “I heard about this Abbot Moses and came out here to meet him. And an old man heading for Egypt ran into us, and we asked him where was Abbot Moses, and he said to us: “What do you want with him? The man is a fool and a heretic!” When the clerics heard this, they asked: “What kind of old man was this, who said such things to you about the holy man?” The judge said, “He was a very old elder with a long black robe.” The clerics said, “Why, that was Abbot Moses.”2

Once a monk committed a sin, and so the elders assembled, and sent for Abbot Moses to join them. He, however, did not want to come. The priest sent him a message, saying: “Come, the community of the brothers is waiting for you.” So Abbot Moses arose and started off. And taking with him a very old basket full of holes, he filled it with sand, and carried it behind him. The elders came out to meet him, and said: “What is this, Father?” Abbot Moses replied: "My sins are running out behind me, and I do not see them, but today I come to judge the sins of another!” When the elders heard this, they said nothing to the brother who had sinned and instead pardoned him.3

One of the great things about holy foolery is the redirection. In Abbot Moses’ case, these redirections were away from the false piety of our self-santifications to true humility, and in turn, redirecting our affections away from the self toward God. These “show without telling” lessons point us to live by example and punchlines.

A more potent version of how we can be Holy Fools is in a story told by David Lamotte in the poem “White Flour.” Once there was a Ku Klux Klan rally in Knoxville, Tennessee. But instead of countering hate with hate, there formed a different kind of protest: clowns. Rather than robbing it of its potency, you can read the full poem on David Lamotte’s website.

When the Church thinks about what kind of ship of fools we want to be, we aspire to creative love and playful joy that we can’t always live up to. We should be realistic that we are often a ship that can’t get out of its way. And yet, we are still Christ’s body, and in turning and returning to Christ, we can return to God’s foolish wisdom as the disciples did on the Sea of Galilee.

Thank God it’s none of us fools are in charge of the Church. It is only the “strong weakness” of Jesus Christ who is the head of his Body. As we figure out how we can best be his Body to our community and our world, a ship of holy fools, let us be wise as serpents, innocent as doves, and maybe even have as much fun as clowns at a hate rally.

Thomas Merton, Wisdom of the Desert, 70.

Merton, 36.

Merton, 40.

Thanks for the mention, Joe. Wonderful history and imagery in the ship of fools, I’ve never heard of that. Reminds me of this image from Augustine, fitting to think of the ship of fools being built from the wood of the cross: “Toil passes, and rest will come; but rest only through toil. The ship passes, and you arrive home; but home only by means of the ship. We are sailing the high seas, after all, if we take account of the surges and storms of this world. The reason, I am convinced, that we are not drowned is that we are being carried on the wood of the cross.”